CORPORATE OVERVIEW

Texas Instruments is a 67-year old, 10-billion dollar, multi-national company with over 40,000 employees in 26 countries. Historically it has had major product lines in such diverse areas as geophysical oil exploration, consumer products such as calculators and computers, software point-of-sale systems, digital military radar and missile systems and, of course semiconductor products. 1997 saw a major change in strategic direction as we divested ourselves of ancillary product lines and focused on our core competency - semiconductors and Digital Signal Processing solutions.

Although TI has always been heavily involved in technical standards, it is only within the last decade that we have begun to actively coordinate and manage that participation. The remainder of this article addresses:

Standards - the running joke is "Standards are wonderful; there are so many to choose from." There are domestic standards, regional standards, international standards, treaty standards, accredited standards, regulatory standards, etc. etc. etc. Over and above the confusing nomenclature itself is the variety of ways individual standards are used. The very same document may be used, by different sets of people, as a technical specification, a purchase specification or a non-tariff trade barrier used to encourage the use of a country's internal products over those which could be imported.

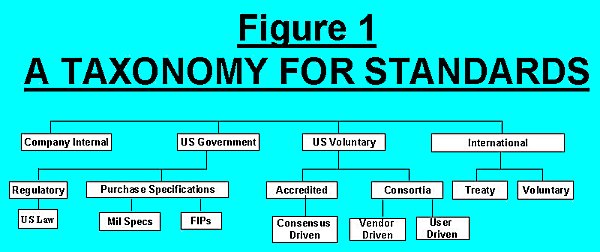

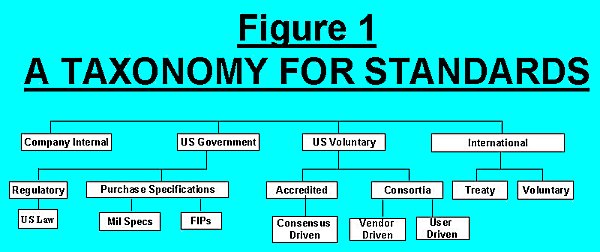

One possible taxonomy of standards, and the one the author prefers to use, is given in Figure 1.

Several comparisons in the given classifications should be noted.

| EXTERNAL vs. INTERNAL | External standards are those developed outside the company.

Internal standards are those standards which are developed by a company for its own purpose. While there are legitimate uses where proprietary issues are concerned, internal standards often exist simply because the implementer did not know that there was an external standard covering the same subject. |

||||||||||||||

| REGULATORY vs. VOLUNTARY | Regulatory standards are usually written by government agencies and

enforced by law with violations resulting in civil or criminal legal action.

Voluntary standards, on the other hand, are written by industry professionals. While some voluntary standards become "regulatory" by virtue of their being cited in building codes, regulations, etc., adherence to most is ensured only by market pressures. These pressures, however, are significant and must not be underestimated. Outside the U.S., the distinctions between voluntary and regulatory standards are less defined. Even though they may be developed largely by volunteers, International Standards often have the force of law in many countries. |

||||||||||||||

| ACCREDITED vs. CONSORTIA | Accredited standards are those developed under the auspices of a recognized

oversight body which ensures that all interested parties have an opportunity

to participate and that due process, including the right to appeal, is

followed during the development. Consortia standards do not have to meet

either of these requirements.

The basic tradeoffs of accredited standards vs. those developed by consortia are shown in Figure 2 below. Both types are of importance to TI and we make no real distinction between them as far as our participation.

|

||||||||||||||

The environment in which these standards are developed is depicted in Figure 3.

The acronyms in the figure are largely unimportant1 - the important thing is that there are overlapping layers of standards developers. Innermost are national standard bodies, one per nation (in the US it is the American National Standards Institute). Then there are regional standards developers, representing geographical groupings of countries (such as the European Union or Pacific Rim countries). Finally there are the three global standards developers - the IEC (International Electrotechnical Commission), ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) and the ITU (International Telecommunication Union). ISO and IEC have a Joint Technical Committee (JTC 1) which is responsible for all Information Technology issues. The ITU is a treaty organization while ISO and IEC are voluntary organizations

The process by which standards are developed within this environment is perceived, somewhat erroneously, to be both lengthy and complex. However, both industry and the standards developing organizations recognize that the development process can be streamlined. Major improvements have been made over the last 15 years and are continuing to be made today. The growing importance of standards as a world trade tool has led to the existence of a "positive spiral" (Figure 4) of industrial participation. The "pump" for new standards comes mainly from industry support of individuals who participate in the standards-making process as well as from membership fees charged by the various organizations2.

There is also, unfortunately, the "negative spiral" of non-participation shown in Figure 5. Within some companies or industry segments, this can result in neutral, negative or even antagonistic response on the part of management to becoming involved in standards development.

It should come as no surprise that in today's marketplace a successful corporate strategy must take global standards into account to ensure international acceptance of products and to successfully address meta-issues such as Quality, Environment, Conformity Assessment, Health, Safety and Human Factors. But given the shear number of standards development activities and given that participation in them is expensive in both dollars and time, there is simply no way that Texas Instruments can participate in all of the committees and organizations which affect us.

We have to identify the ones which we feel will benefit us the most or provide us with the most opportunity for impact. This brings us to Strategic Standards Management.

Strategic Standards Management

- It takes a Plan

| Alice: Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from

here?

Cheshire Cat: That depends a good deal on where you want to get to Alice: I don't care much where - so long as I get somewhere Cheshire Cat: Then it doesn't matter which way you go. |

As with most companies operating in the voluntary standards arena, TI has a choice to either participate - or not - in the development of standards which affect our business. This is a business decision and there are the usual pros and cons of any business decision. If we do participate, we have at least some say in and control over the standards which influence our product lines but at the expense of significant short-term costs that have weak traceability on long-term return. On the other hand, if we choose not to participate, then the resulting cost avoidance provides an immediate profit improvement but at the expense of lack of self-determination in our long term product destiny.

Throughout its 67-year history, TI has chosen to participate quite heavily in the standards community and we continue to do so with over 300 employees participating in over 500 standards developing committees worldwide. We strongly believe that this represents a long-term strategic investment which more than offsets the short-term expenses inherent in standards involvement. We are managing this activity using the techniques of Strategic Standards Management (SSM)3.

Put simply, SSM involves recognizing that standards are more a business issue than a technical one. Global standards are used as a basic vehicle for communicating requirements worldwide to customers and suppliers. They also serve as fundamental tool in developing marketing strategies: What new products can be developed to standards that already exist? What new standards are under development which affect existing products? How can new standards be used to enlarge existing or create new market spaces?

The benefits to be gained by the strategic management of standards participation can be generally categorized as tangible profitability resulting from increased sales of components and services, and intangible benefits arising from an increased understanding of both user needs and general industrial and competitive directions. Both categories are difficult to quantify, but there is no doubt that planned participation is more to TI's advantage than against it. There is also no doubt that failure to explicitly manage standards participation in the formal strategic planning and global design review processes will result in a competitive disadvantage in today's global marketplace.

Unfortunately, these benefits do not come overnight. Similar to the Quality Journey of the 70's , TI considers itself to be on the Standards Management Journey depicted in Figure 6. We have moved past Stage One where, although we participated heavily in technical standards, we were essentially incompetent in terms of managing that participation and largely unaware of the incompetence. As we began to more effectively manage our standards involvement, we've moved through Stage Two and are currently in Stage Three. The transition to Stage Four, where the management of standards is automatic, unconscious and as much a part of the TI culture as Environment, Quality and Safety, is much more difficult and we still have a lot of work to do before we arrive.

So where are we?

TI'S CORPORATE STANDARDS PROGRAM

Even though our corporate culture is one of divisional autonomy and decentralization, there are certain areas where it makes sense to have a corporate office which sets policy for the entire company. These include legal, environmental and product safety - areas where we want to have a consistent stance no matter which product line we're talking about. Standards management is a similar subject and there is ample justification for some sort of centralized standards office to serve as a focal point for the variety of standards activities in which we are engaged and to address issues such as:

On the other hand, while TI does want some level of inter-divisional control, we do not want a large bureaucracy in corporate overhead. This has led us to implement, as depicted in Figure 7, a standards program consisting of a small centralized Standards Office coupled to the product divisions via a formal Corporate Standards Council. The Council is "corporate" only in the sense that it represents Texas Instruments Incorporated - its membership is representational as will described later.

Together, the Council and Office loosely manage TI's standards activities as an on-going process. This process, depicted in Figure 8, includes components for assessing our progress and for tracking those standards we are not actively participating in today. The bottom-line goal is threefold:

By being a member of the appropriate coordination and oversight management committees we are made aware of upcoming changes in areas of importance to our businesses and this information can be fanned out to the product divisions via the Council. Additionally, by maintaining the visible and sustained presence of Step 7, TI is in a better position to be able to react to rapidly changing events.

As previously indicated, the Council's membership is representational and composed of three types of members:

The Council does most of its work, serving as a clearing-house for standards related issues within the company, via email and an internal intranet which serves as an information distribution mechanism. It is very likely that different product groups will have different needs and levels of involvement in the standards community. This is entirely appropriate. However, without adequate knowledge of what is taking place in the standards arena, they cannot make intelligent decisions about which activities will benefit them the most. Even if the participation level in a particular organization is zero, that organization should still be aware of the interest level of others, both internal and external to TI. The Council helps it do so.

The Standards Office itself, although not large, serves to facilitate the creation of an effective standards-orientated infrastructure which supports the needs of the product divisions by:

While it is clear that the technical participation in individual standards activities must continue to come from the affected product divisions, the Standards Council and Office together coordinate that participation in order to maximize the return on an investment that already exists. If the they did nothing more than make everyone aware of what is going on, we would be a major step ahead.

THE FUTURE

As stated previously there is a lot of work to do before we reach Stage 4 of Figure 6, but it breaks down into three major pieces.

First, improvements in the expectations and effectiveness of the 300+ technical participants and their immediate management are always desirable. From TI's standpoint, the ideal standards participant should be:

Second, we need to complete the integration of a standards program in which the Standards Office serves as an underlying substrate to the business units, tying together all of the various corporate offices which may interact with the actual technical participants. Although most have been identified, not all are in place today - Figure 10 depicts the eventual relationships we would like to establish.

In addition, the Office should represent TI in venues which are not directly product related and which may not even be technical in nature. TI's "good citizen" status within the standards making community includes working relationships with ANSI and US government offices such as the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), the EPA and the Department of Commerce.

Third, TI could better utilize its multi-national status. We have sites in 26 countries and potentially we could have a TI employee on each of those national bodies. While it is entirely possible that the national position on a particular issue could differ from the preferred TI position, we would still have a better to opportunity to promote our viewpoint than we have today. This is an expensive expansion of our current practice and its potential value and effectiveness are still being evaluated.

SUMMARY

The mechanism of a small standards office coupled with a representative council has proved to be an optimal solution within TI's culture. It has effectively solved to the problem of how to make the most of a broad range of participation without adding an undue burden or expense to the work of the participants. The effectiveness of both is being continuously reviewed and they will continue to evolve to meet the needs of the company.

Additional Reading

Clyde R. Camp received his B.S.E.E. from Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1969, and his Master's Degree in computer science from Southern Methodist University in 1975. He may be reached via email at c.camp@ieee.org.

His 29-year career at TI has included H/W and S/W design of real-time embedded computer systems within TI's Military Products Division, managing TI's Industrial Systems Division's System Engineering department, work with the Languages and Real Time Systems development in the Computer Science Center's Computer Systems Laboratory in Dallas. He currently manages TI's Corporate Standards Office as Director of Standards.

Clyde is a registered professional engineer in the state of Texas, a Senior Member of the IEEE and has been active in the standards arena for the past 15 years holding numerous standards-related positions on various ISO Technical Advisory Groups for the US and in the Computer Society, the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers and the National Committee on Information Technology Standards.

At home, Clyde and his family enjoy science fiction, astronomy, woodworking and the desert Southwest.

This article originally appeared in the December 1997 issue of ASTM Standardization News and, with the exception of the Global Standards Overview section, was reprinted in the May 1998 issue of the ISO Bulletin.